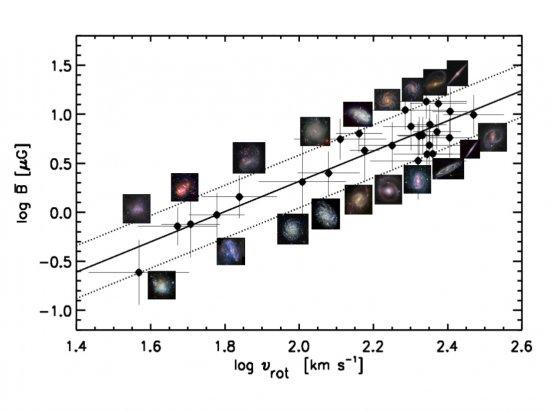

Magnetic fields are present on all scales in the Universe from planets and stars to galaxies and galaxy clusters, and even at high redshifts. They are important for the continuation of life on the Earth, the onset of star formation, the order of the interstellar medium, and the evolution of galaxies. Hence, understanding the Universe without understanding magnetic fields is impossible. The origin and evolution of cosmic magnetic fields is among the most pressing questions in modern astronomy. The most widely accepted theory to explain the magnetic fields on stars and planets is the α-Ω dynamo theory. This describes the process through which a rotating, convecting, and electrically conducting fluid can maintain a magnetic field over astronomical timescales. On larger scales, a similar dynamo process could produce coherent magnetic fields in galaxies due to the combined action of helical turbulence and differential rotation, but observational evidence for the theory is so far very scarce. Putting together the available data of non-interacting, non-cluster galaxies with known large-scale magnetic fields, we find a tight correlation between the strength of the large-scale magnetic field and the rotation speed of galaxies. This correlation is linear assuming that the number of cosmic-ray electrons is proportional to the star formation rate, and super-linear assuming equipartition between magnetic fields and cosmic rays. This correlation cannot be attributed to an active linear α-Ω dynamo, as no correlation holds with global shear or angular speed. It indicates instead a coupling between the large-scale magnetic field and the dynamical mass of the galaxies. Hence, faster rotating and/or more massive galaxies have stronger large-scale magnetic fields. The observed correlation shows that the anisotropic turbulent magnetic field dominates the large-scale field in fast rotating galaxies as the turbulent magnetic field, coupled with gas, is enhanced and ordered due to the strong gas compression and/or local shear in these systems. This study supports a stationary condition for the large-scale magnetic field as long as the dynamical mass of galaxies is constant.

Advertised on

References

It may interest you

-

Type 2 quasars (QSO2s) are active galactic nuclei (AGN) seen through a significant amount of dust and gas that obscures the central supermassive black hole and the broad-line region. Here, we present new mid-infrared spectra of the central kiloparsec of five optically selected QSO2s at redshift z ∼ 0.1 obtained with the Medium Resolution Spectrometer module of the Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) aboard the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). These QSO2s belong to the Quasar Feedback (QSOFEED) sample, and they have bolometric luminosities of log L bol = 45.5 to 46.0 erg s −1 , global starAdvertised on

Type 2 quasars (QSO2s) are active galactic nuclei (AGN) seen through a significant amount of dust and gas that obscures the central supermassive black hole and the broad-line region. Here, we present new mid-infrared spectra of the central kiloparsec of five optically selected QSO2s at redshift z ∼ 0.1 obtained with the Medium Resolution Spectrometer module of the Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) aboard the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). These QSO2s belong to the Quasar Feedback (QSOFEED) sample, and they have bolometric luminosities of log L bol = 45.5 to 46.0 erg s −1 , global starAdvertised on -

Understanding the magnetic field in the corona is key for explaining the fascinating physical processes occurring there. However, the extreme conditions in the outer solar atmosphere hamper the possibility of acquiring observations with enough quality to infer the coronal magnetic field. Analyzing observations of overdensities of cold plasma supported by coronal magnetic fields, including filaments and prominences, allows us to understand such magnetic fields and their interaction with plasma. In this study, we have analyzed an active region prominence, a type of prominence that has barelyAdvertised on

Understanding the magnetic field in the corona is key for explaining the fascinating physical processes occurring there. However, the extreme conditions in the outer solar atmosphere hamper the possibility of acquiring observations with enough quality to infer the coronal magnetic field. Analyzing observations of overdensities of cold plasma supported by coronal magnetic fields, including filaments and prominences, allows us to understand such magnetic fields and their interaction with plasma. In this study, we have analyzed an active region prominence, a type of prominence that has barelyAdvertised on -

Dormant black holes in X-ray transients can be identified by the presence of broad Hα emission lines from quiescent accretion discs. Unfortunately, short-period cataclysmic variables can also produce broad Hα lines, especially when viewed at high inclinations, and are thus a major source of contamination. Here we compare the full width at half maximum (FWHM) and equivalent width (EW) of the Hα line in a sample of 20 quiescent black hole transients and 354 cataclysmic variables (305 from SDSS I to IV) with secure orbital periods (Porb) and find that: (1) FWHM and EW values decrease with PorbAdvertised on

Dormant black holes in X-ray transients can be identified by the presence of broad Hα emission lines from quiescent accretion discs. Unfortunately, short-period cataclysmic variables can also produce broad Hα lines, especially when viewed at high inclinations, and are thus a major source of contamination. Here we compare the full width at half maximum (FWHM) and equivalent width (EW) of the Hα line in a sample of 20 quiescent black hole transients and 354 cataclysmic variables (305 from SDSS I to IV) with secure orbital periods (Porb) and find that: (1) FWHM and EW values decrease with PorbAdvertised on