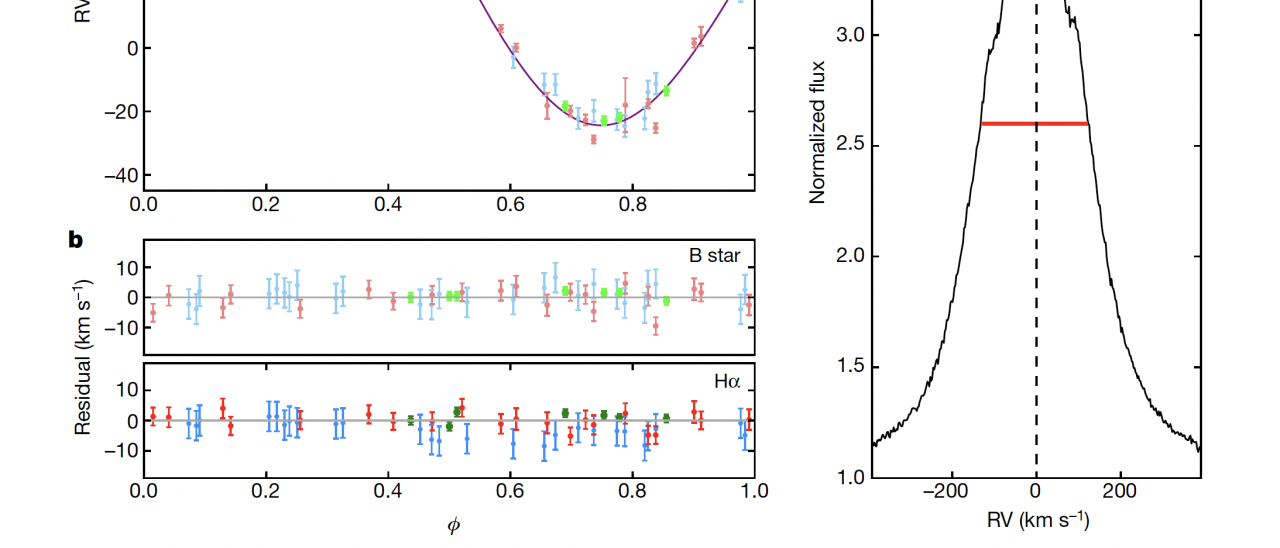

All stellar-mass black holes have hitherto been identified by X-rays emitted from gas that is accreting onto the black hole from a companion star. These systems are all binaries with a black-hole mass that is less than 30 times that of the Sun. Theory predicts, however, that X-ray-emitting systems form a minority of the total population of star–black-hole binaries. When the black hole is not accreting gas, it can be found through radial-velocity measurements of the motion of the companion star. We report here radial-velocity measurements taken over two years of the Galactic B-type star, LB-1. The star was initially discovered during a monitoring campaign with the 4-m telescope LAMOST and subsequently studied in more detail with the 10-m class telescopes GTC and Keck. We find that the motion of the B star and a superimposed Hα emission line (see figure) require the presence of a dark companion with a mass of 68 solar masses, which can only be a black hole. The long orbital period of 78.9 days shows that this is a wide binary system. For comparison, black holes detected in X-ray binaries have masses in the range 5-15 solar masses. On the other hand, gravitational-wave experiments have detected black holes with several tens of solar masses. However, the formation of a ~70 solar mass black hole in a high-metallicity environment is extremely challenging within current stellar evolution theories. This would require a significant reduction in wind mass-loss rates and overcoming the pair-instability supernova phase, which limits the maximum black hole mass to less than ~50 solar masses. Alternatively, the black hole in LB-1 might have formed after a binary black hole merger or other exotic mechanisms.

a) radial velocity curves and orbital fits for the B-star (purple) and its dark companion (orange), the latter extracted from the wings of the Hα emission (panel c). b) Residuals obtained after subtracting the best orbital models from the velocity points.